DARPA wants to create ‘self-healing’ firmware that can respond and recover from cyberattacks – CyberScoop

Imagine, for a moment, that your network is hit with ransomware.

One of your employees clicked on a malicious link and now your network is compromised, data is encrypted and most of the organization’s systems are locked or offline.

Then imagine if instead of assembling an incident response team, notifying the board and contacting law enforcement, the forensic sensors in your device’s firmware spring to life. They begin healing your network, restoring locked files, and communicating with other systems to collect forensic data.

The firmware then analyzes the data to identify how the attackers entered and exploited system weaknesses, then blocks those vulnerabilities to prevent future breaches through the same entry points.

While it sounds like science fiction, researchers at one of the Pentagon’s top cyber innovation hubs are attempting to prove the idea is more than a pipe dream.

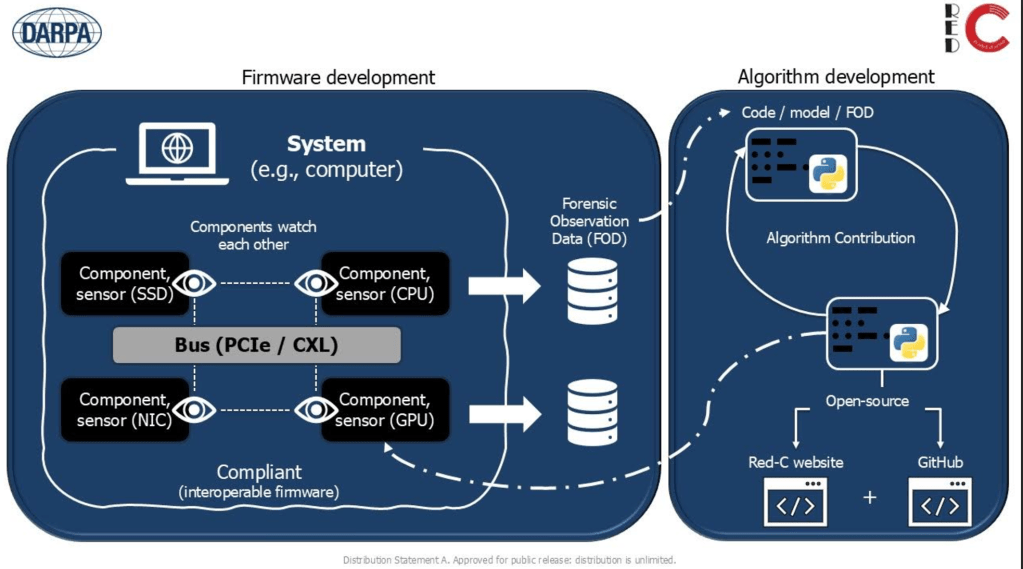

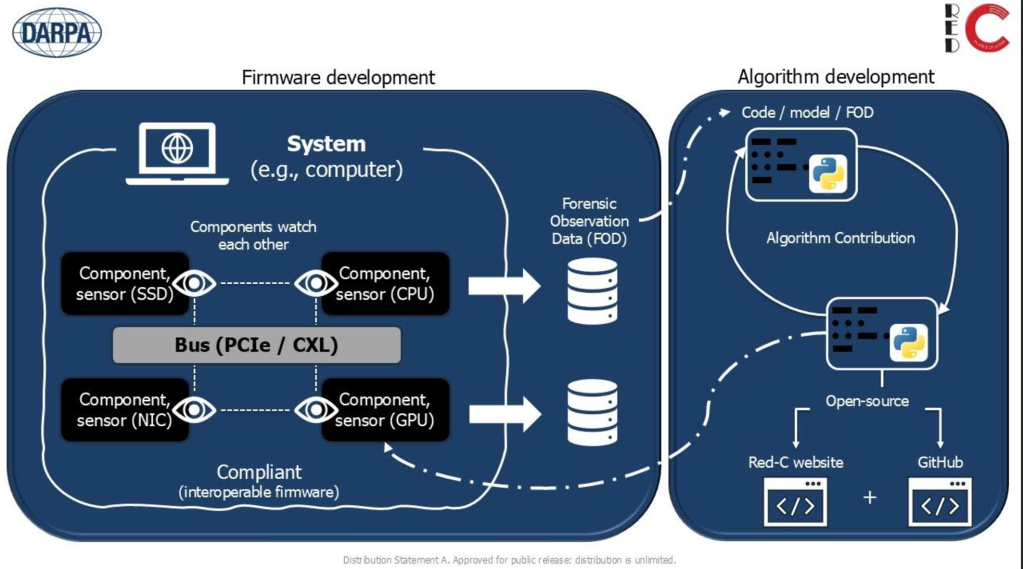

Red-C, a new project being rolled out by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, seeks to build new defenses into bus-based computer systems, which are firmware-level systems used in everything from personal computers to weapons systems to vehicles.

“For far too long there’s been a missing layer in our security onion. We haven’t thought about how a computer would defend itself,” said Bernard McShea, DARPA’s program manager for RED-C. “This idea of a distributed, embedded layer of security at the bus level is a new thing that’s been missing for a very long time.”

Bus systems — the “B” in “USB” — are responsible for transferring data between different components of a computer system. Red-C is DARPA’s quest to reengineer these communication highways to create a “neighborhood watch” system between different components so they can identify and respond to attacks in real time.

Because their role is elemental to most computer operations, bus-based systems often carry the highest levels of trust, making them an attractive single point of failure for attackers to compromise. On the recovery front, bus systems often carry enough data to identify the files on your computer and relay this information to other components, but lack the capacity to store the actual content or restore the data to a previous state.

The process starts with rewriting the firmware used in many computers to create forensic sensor capabilities for each component, allowing them to cooperate with each other and monitor for signs of compromise or malicious activity. DARPA’s work focuses on two specific types of buses: Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) and Compute Express Link (CXL).

This kind of on-system monitoring integrated directly into a device’s firmware could be as effective, or even moreso, than many external cybersecurity and antivirus tools. The built-in approach could provide massive security benefits, especially for the smallest or most resource-limited organizations.

Additionally, DARPA believes this new firmware could go beyond just monitoring for malicious cyber activity. It could also be used to restore data and files to previous states, making it more difficult for, say, ransomware actors to lock up systems and create downtime that can put added pressure on victims to pay the ransom.

“I think the application to ransomware, even when people have been attacked and whether or not they paid the ransom or had backups, just being down for a few days is absolutely devastating monetarily,” McShea said. “Not only for multi-million-dollar companies but any mom-and-pop shop that updates or buys equipment with Red-C firmware, they now have the ability to defend themselves.”

Bus-based security faces real roadblocks

DARPA is inherently tasked with pushing the boundaries of technology, and thus rarely focuses on problems with simple solutions. The agency anticipates that many of its projects won’t become revolutionary, which is intentional. DARPA does not strive for a high success rate in its projects because that “indicates risk is not being taken for exploratory research and development,” according to a financial report published last year. As former Director Charles Herzfeld said of the agency’s work in 1975, “when we fail, we fail big.”

To that end, achieving Red-C’s goals will require solving several technological and logistical challenges over the next two years. Some of the questions the program aims to answer are: How would such a system identify zero-day malware? How can firmware be rewritten to best restore and patch a system while it’s still running and changing states?

Further, there’s a chance that any changes or processes introduced by Red-C could themselves alter systems or networks in ways that make them more vulnerable to different kinds of attacks, a concern McShea said is “not easily dismissed.”

Even if these technological obstacles are surmounted, Red-C firmware would still need to be adopted and embedded within industry standards to ensure that manufacturers use it in their hardware. That is a real challenge, and the cybersecurity landscape is littered with great ideas that struggle to make a large impact because of lack of widespread adoption.

Curtis Dukes, a computer scientist who previously led the National Security Agency’s Information Assurance Directorate (now called the Cybersecurity Directorate), told CyberScoop that the two bus systems selected by DARPA — PCIe and CXL — currently “don’t actually have any type of infrastructure” to handle the kind of tasks the agency is trying to assign them.

“What’s going to be hard about this is for companies to actually build that into existing busses,” said Dukes, now executive vice president and general manager at the nonprofit Center for Internet Security. “They’re not just going to be able to take existing busses you find on computer systems with no changes necessary. It’s going to require changes on the bus architecture itself, which means companies have to retool for that to provide those products.”

He also mentioned that finding a way to patch and restore hacked systems to their original state without reversing legitimate changes to a system is crucial. Additionally, avoiding the creation of a “Skynet”-like surveillance apparatus that introduces its own security risks is another complex issue yet another sticky problem that will need to be addressed.

Despite the skepticism, Dukes applauded the effort, noting that if DAPRA achieves even a fraction of the project’s goals, it could improve the overall cybersecurity ecosystem and push more research around bus-based security in the private sector.

“My view is even if DARPA only gets a tenth or 20% of the benefits in this research, that is still going to [push] young, innovative companies to then take that and be able to innovate on that,” Dukes said.

McShea, for his part, readily acknowledged similar challenges. DARPA is in the beginning stages of research around the technical breakthroughs needed to make Red-C work, and expressed a strong desire to partner with private-sector companies on the front-end to ensure that any technology produced can be easily adopted and integrated by industry.

DARPA held an industry day with businesses this week to introduce the program and develop buy-in among industry. The goal is to develop a prototype of the technology by the end of the 24-month program that is “reasonably well developed to be tested and used by others.”

The next step would be industry cooperation, which McShea argued could both speed up adoption and create a market effect where manufacturers with Red-C firmware have a competitive advantage with customers.

“I’d really like hardware manufacturers to form teams,” he said, “and come onto the Red-C program.”

The post DARPA wants to create ‘self-healing’ firmware that can respond and recover from cyberattacks appeared first on CyberScoop.

–

Read More – CyberScoop